St. Luke's Health Uses AI to Cut Cardiac Arrests and ICU Transfers

Anna Stone was going through the first rounds of her nursing shift at St. Luke’s Upper Bucks Campus when she noticed a patient's heart rate was elevated, a sign that they could be at risk of a cardiac emergency. Before she could check the patient’s chart and decide whether to call for help, a critical care doctor rushed to the patient’s bedside.

A drop in the patient’s oxygen levels had been detected by a monitor that uses artificial intelligence to continuously evaluate vital signs. This triggered an automatic alert for the hospital’s critical care team to send help.

The AI tool is designed to assist doctors and nurses in identifying patients whose conditions are deteriorating — often before visible signs of distress appear — allowing them to intervene earlier. This approach has led to a 34% decrease in cardiac arrests and a 12% reduction in patients experiencing rapid declines requiring urgent ICU transfers between 2022 and 2024, according to St. Luke’s.

Survival rates among cardiac arrest patients increased from 24% to 36%. St. Luke’s experiment with a program called the Deterioration Index, developed by healthcare software giant Epic, is one of the latest examples of hospitals integrating artificial intelligence into their patient care processes.

In other Philadelphia-area initiatives, Jefferson Health and Penn Medicine have introduced ambient listening tools that record conversations between doctors and patients, extracting key details to create well-organized visit notes.

St. Luke’s has been using its AI monitoring system across all 16 of its campuses, including Quakertown, Upper Bucks, and Grand View, which the health system acquired in July. The initiative has been recognized by The Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania, the region’s largest hospital industry group, with an award for safety and quality improvements that enhanced patient care while reducing hospital costs.

Using AI to Predict Emergencies

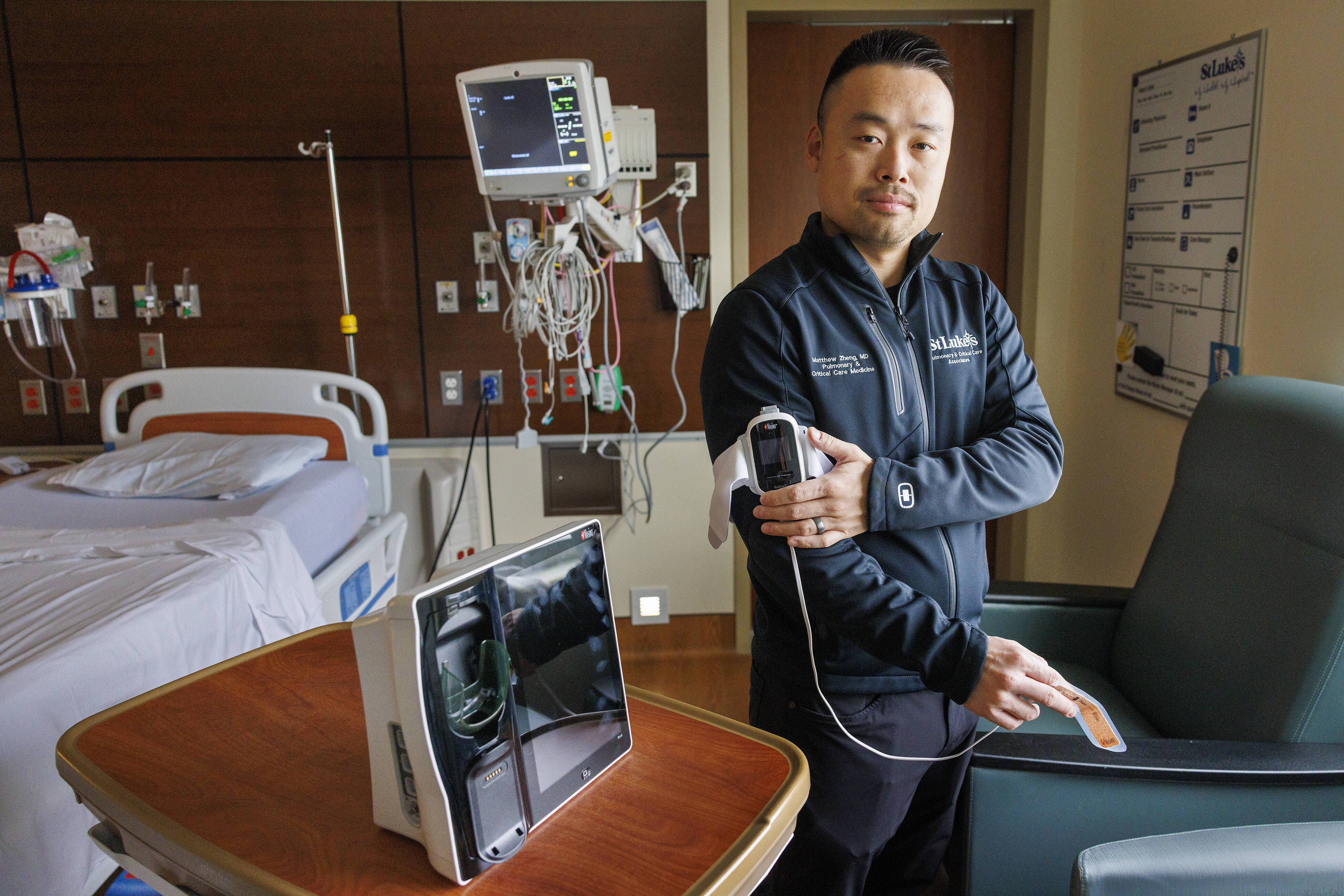

The monitoring device, which attaches to a patient’s finger, records and continuously updates patients’ electronic medical records with vital metrics such as heart rate, blood pressure, and lab work results. Using this matrix of data points, it assigns each patient a “deterioration index” — a score between 0 and 100 indicating their overall stability — and automatically alerts critical care when the score rises too high.

It is not intended to replace in-person monitoring but serves as an extra set of eyes when nurses are away from their bedside. What’s more, the sophisticated technology can detect nuanced changes in a patient’s status before physical signs of distress appear.

“We would ideally like to intervene on these patients before they reach a point where the intervention isn’t that helpful,” said Matthew Zheng, a critical care doctor at St. Luke’s Hospital — Upper Bucks. “Our nurses work very hard, but they can’t be in the same room all the time.”

When a patient’s “deterioration index” rises above 60, the device sends an alert to the hospital’s virtual response center — a remote hub where a nurse monitors three screens showing the status of all patients. Alerts may also be sent directly to a patient’s care team or the rapid response unit, if the AI monitoring detects that a patient is quickly deteriorating and needs emergency care.

“What that’s allowed is for us to have a proactive response instead of being reactive to patients,” said Charles Sonday, an associate chief medical information officer at St. Luke’s who leads AI initiatives.

Stone, the Quakertown nurse, said having the tool to constantly watch over patients while she’s out of their room is reassuring. Doctors like that it enables them to quickly get up to speed on the status of a patient they transferred out of the ICU, and respond more immediately to their new medical needs, said Zheng, the critical care doctor.

St. Luke’s plans to continue fine-tuning the technology and customizing it to meet the unique patient profiles of each of its campuses, which span 11 counties and two states, from the Lehigh Valley to New Jersey.

The social and economic factors that affect patient health, such as pollution and illness rates, vary significantly across the health system’s sprawling network, Sonday said. The system will also explore customizing the tool for specialty services, such as pediatrics and behavioral health.